A year ago at this time, “The Post” was one of the most marketed and publicized movies in the United States. The film retold the story of The Washington Post’s coverage of the Pentagon Papers after they were first shared with The New York Times, resulting in a landmark Supreme Court case involving both newspapers in 1971. The Supreme Court ruled in New York Times Co. v. United States that the government did not meet the standard needed to establish prior restraint and justify withholding of continued publication. The 6-3 ruling went in favor of The Post and The Times.

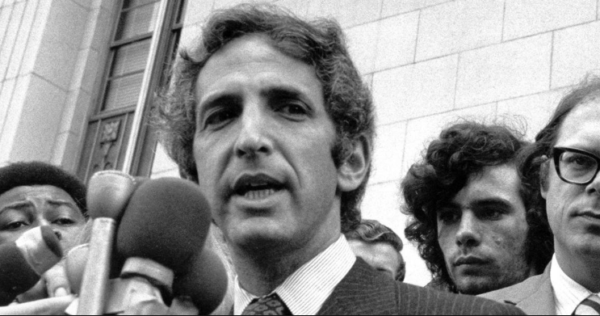

“The Post” focused on the journalists at the heart of the Pentagon Papers stories and the impact of their disclosure in the worlds of politics and journalism, but the man who leaked the papers to Neil Sheehan of the NYT and Ben Bagdikian of WaPo also owned a considerable place in the story. That dimension of “The Post” did not gain the traction I had hoped it would.

That man — that part of the story — is worth discussing, roughly one year after “The Post” opened at theaters.

Daniel Ellsberg became a peace activist in the fullness of time, a countercultural figure and an anti-establishment voice. He became, in the course of his life, the embodiment of what a progressive anti-war activist either aspires to be or expects to see from others in positions of influence.

I cannot look at Ellsberg’s life without marveling at how a young man in the 1960s was able to uproot his existence and risk long-term imprisonment to disclose what he felt, in his conscience, were truths that had to be shared with the American people.

Ellsberg was an insider, working for the RAND Corporation — a prominent think tank created in 1948 to align military planning with various research and development strategies. RAND was developed in and from the military-industrial complex, exploring a combination of policy, strategy and technology to maintain a strong connection between the military and private industry.

Ellsberg had done field work in Vietnam for the U.S. Department of State. The documents which would become known as the Pentagon Papers were part of a Vietnam Study Task Force commissioned by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara in 1967. Ellsberg — a former United States Marine who began working at RAND Corporation in 1958 — was part of the system. He was embedded deep inside it.

McNamara, Dean Rusk, and scores of other important people in the Departments of State and Defense went down with the Vietnam War, digging in their heels to continue to push for the war long past the point when a decisive and productive military victory ceased to be a realistic and attainable goal. David Halberstam wrote about these stubborn men in his seminal book, “The Best And The Brightest.”

It is natural to “go down with the ship,” to insist that the projects or goals which consumed the prime years of a public career were worth fighting for. It is natural — as we see in works of great literature, film or television — for human beings to conclude that they have spent so much of their lives in service of certain ideas that they feel they can’t turn around and reverse course. It’s too late.

Specific ideas — in this case, American exceptionalism — can be so powerful and convincing, both intellectually and culturally, that longtime public servants can’t see a way out of them. They can’t imagine abandoning the notion that America is an exceptional nation, and everything that means.

Daniel Ellsberg found a way out. He was able to see that the Vietnam War — which he had worked to advance in its earlier stages — had become terribly wrong and dishonestly waged.

This doesn’t make McNamara more vile. It makes Ellsberg more remarkable.

This leads me to a basic point about George Herbert Walker Bush, the 41st President of the United States, who died on Nov. 30 at the age of 94, and whose public career was revisited over the past week before being laid to rest in Houston on Dec. 6.

Bush 41 presided over a lot of wrongdoing, briefly summarized by The Intercept’s Jeremy Scahill here:

https://twitter.com/jeremyscahill/status/1071856051102932992

The substance of Bush’s actions as a public figure is considerable, in some good ways (the tax increases he approved as president) but also in the bad ways outlined by Scahill. In thinking about how to assess Bush’s life, my fundamental response is that his life was complicated.

The good side of the man should not be ignored: the way he was there for James Baker — “Bake,” his best friend — when Baker’s wife died and left a young man to care for his kids. That’s the kind of friend we would all want to be.

Bush’s letter to Bill Clinton upon leaving the White House and making way for the young Arkansan is a study in grace and the peaceful transfer of power. We should all want departing presidents to wish their successors well, in the way Bush 41 modeled.

George H.W. Bush was a skilled diplomat who cultivated personal relationships, deflected attention from himself, and exhibited a lot of personal qualities we ought to want for ourselves.

Yet, as with Bob McNamara in the 1960s and Madeleine Albright under Bill Clinton and Leon Panetta under Barack Obama, people who carved out long careers in public service — and who might have been the warmest, most affable people if sitting down to have a beer and a steak with them — nevertheless did a lot of bad things while serving U.S. Presidents in various capacities, chiefly in the Departments of Defense or State.

These people did monstrous things… but I hesitate to call them monsters.

Does that seem like a pointless distinction? I understand if it does. To be sure, part of the purpose of writing this column is to make sure history doesn’t forget the atrocities these public servants presided over.

However, I bring up Bush 41 and these other public figures to contrast them to Daniel Ellsberg. This contrast is meant to amplify what I said above: This doesn’t mean these various figures are that much more horrible. It amplifies, again, how remarkable it is and was — and will be — for Ellsberg to have been morally and ethically awake enough to change his worldview and actions.

It is so extraordinarily difficult to immerse oneself in a given culture or environment, make a lot of money within it, and have a prominent position… and then give it all up because one sees the error of one’s ways. That isn’t an unheard-of path — Ellsberg followed it — but it is not the normal path.

As I reflect on George Herbert Walker Bush’s life and career — with the military in World War II, with the CIA, as Vice-President and President of the United States, in the behind-the-scenes Carlyle Group, and elsewhere in the machinery of power and influence — I struggle to see a time when one could have reasonably expected Bush 41 to have had his “Ellsberg moment.”

Would it have been great if he did? Sure… but given the experiences Bush 41 had, where could that moment have occurred? Let’s remember that World War II, for all the flaws one could point out, did end with the defeat of Hitler and Japan. If you were part of that war effort in any real way and you then lived to see V-E Day and then V-J Day in 1945, you very likely thought the effort was worth it. Your life might have changed at some point in the future, but it would have been hard for any outsider to come in and insist, “You know, George, you HAVE to oppose war now. It’s the only obvious choice.”

As much as war is — in the words of Pope John Paul II — “always a defeat for humanity,” how can one step into a life such as the one lived by George Herbert Walker Bush and demand that he should have become a different person, and that he should have become suspicious of the United States Government as Ellsberg did?

The substance of George Herbert Walker Bush’s actions as a public figure and leader — while owning several powerfully good and productive moments — contained quite a lot of black marks. The many people who suffered or died at the hands of those actions and policies should not be forgotten, ignored, or diminished in an honest recollection of history. Bush 41 and other U.S. Presidents should not be sanitized when they die. Jimmy Carter’s failures as POTUS will need to be noted when he passes away in the coming years. No one would be served by applying a double standard in any direction.

What follows, then, is not “sanitizing” Bush 41’s life so much as putting it in its properly complicated context: While it certainly mattered in a material sense — lives lost instead of saved, weapons used instead of withheld, regions destabilized instead of preserved — that George H.W. Bush couldn’t see through the United States Government’s immoral handling of war and foreign/military policy, I don’t think any person or any idea, including the idea of God (whom I believe in), is served by calling HIM a monster.

Bush 41 was not and is not a monster. We as progressives — or anyone with firmly anti-war views — should not think or talk of him (and others like him) in that way.

The problem — the focus — of this piece is not George H.W. Bush or Daniel Ellsberg. The ultimate point here is that it is immensely difficult for any of us to wrest ourselves away from a pervasive culture and outlook which surround us in the media we consume, the way leaders and influencers present information to us, and the narrow set of experiences we have.

Daniel Ellsberg didn’t become what George H.W. Bush became… but the line between conversion and the retention of the status quo is not easy to cross.

I feel empathy toward the people from past decades who suffered — in Kuwait and Central America — from the actions of George Herber Walker Bush in his public life.

That doesn’t mean I will withhold empathy and affection from Bush, or from his son, Bush 43.

Is this complicated? You bet it is… which is why it is honest and, moreover, necessary.

I wish our mass media outlets could reflect on and assess public lives in this manner.

“The Post” merits a rewatch… but only if you are prepared to view historic figures and episodes through that prism. I’m sure Daniel Ellsberg would agree.