In an urban megalopolis like New York City, environmental issues–like air and water quality–are a daily concern for many New Yorkers. Unfortunately, forcing legislative change in a city this large can be slow. The city’s Green Party (GP) contingent works to make issues like these a priority. However, in Gotham, it isn’t easy being green.

For GP members—or “Greens” as they are nicknamed—getting the party some influence within the city’s halls of government has been no easy task. In upstate New York GP representatives have held positions on town councils, school boards, and have even been mayors. However, that has not been the case in the confines of the five boroughs, and Long Island. Despite the city’s plethora of ecological concerns.

The party originally gained mainstream notoriety in the state during Ralph Nader’s 2000 campaign for the presidency. “In 2000 Ralph Nader was the Bernie Sanders,” says GP representative James Lane. The Harlem native began his affiliation with the organization after long having distaste for local politicians. The party’s platform connected with him on such a level, that it compelled him to go out and actually register to vote–for the first time at 35-years–old. “This is exactly what I was looking for my entire life,” says Lane.

The party’s reputation for responding to environmental issues is warranted, considering recent data found on a key issue that affects many Gothamites—air quality. The city estimated last year that 2,700 premature deaths may occur from the particulate matter (particles produced from vehicle exhaust, combustion engines, and power plants) in the air we breathe. That’s more deaths than there were from murders in 2013. These particles could lead to heart disease, lung cancer and asthma.

During a 2012 New York City Community Air Survey, 60 sites were measured for particle matter. Two Midtown district’s levels were higher than the acceptable standard recently lowered by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The World Health Organizations (WHO) standards are even lower than the EPA’s, and 12 city neighborhoods were not able to meet WHO accepted standards. High poverty neighborhoods in the Bronx, northern Manhattan, and northern Brooklyn had some of the worst cases of air quality, and highest rates of emergency room visits for asthma.

Air quality is a key concern for the GP. “More fuel-efficient vehicles are a piece of the solution, but not as significant as going 100 percent clean, renewable, energy as soon as possible,” says Gloria Mattera, the current co-chair of the party in New York, and secretary of the GP in Brooklyn. Lane believes the city should think outside the box. Suggesting a good start would be to switch city vehicles to recent engine technology based around using grease.

Building furnaces are also a major cause of air pollution. The Clean Heat Program created in 2012, forced building owners to convert to cleaner burning fuels. “Every public building should be retro-fitted to reduce emissions,” Mattera says. The result did decrease sulfur levels in the air, and recently dropped the five boroughs to 36th amongst U.S. cities on the American Lung Associations particle pollution annual listing.

Like Lane, GP members’ desire to address issues like these is what originally got them involved with the party. Mattera also joined during Nader’s campaign in 2000, playing a role as an organizer for the city branch of Labor for Nader. After his failed attempt to become president, she continued on with the party. “I stayed connected to the local Green Party in Park Slope, and became their City Council candidate in 2001.”

Their devotion to the platform pushed both Lane and Mattera to run for public office under the party banner. Lane attempted to run for the position of public advocate in 2013. Mattera made several bids for City Council, representing the 39th District, in 2001 and 2003. As well as attempted to become the Brooklyn borough president in 2005. Even though these runs for office were unsuccesful, progress was made, as Mattera received 20 percent of the vote in 2003, and placed higher than the local Republican.

The election losses however have not deterred the Green Party’s efforts on environmental issues. The city has implemented initiatives like MillionTreesNYC, PlaNYC, and OneNYC to address issues like air pollution, climate change, and sustainable buildings. Yet the question remains, is it just window dressing for mass media, or an adequate response? “The city never does enough to handle any issue. That’s actually why I’m running for public advocate,” says Lane. He believes the city’s attempts at fixing problems is more a show of progressive ideologies for incoming tourists, rather than a true strategy for systemic change.

Air quality is just one of several ecological concerns for the citizens of New York. Pollution of the city’s waterways is a serious problem as well. The 315-mile-long Hudson River is currently an EPA Superfund Site. This means an extreme pollution problem was ignored long enough that the federal government had to step in to fix the issue. Furthermore, the city’s sewage systems are in poor condition. During times of flooding, the runoff is pumped into New York harbors. Riverkeeper, a non-profit organization, found that many city waterfronts and public beaches are unsafe after flooding, due to the sewage runoff in those waters.

Lane suggests the city government should try and work more closely with community organizations, like Sunset Park’s Uprose. The group dates back to 1966 and has long been an example of citizen-lead movements for sustainability. “Work with them [Uprose], and give them a place in city government to actually get the job done,” said Lane.

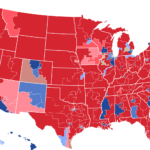

With elections coming in November, the GP understands adjustments to voting laws may be required, to remedy their defeats of the past. Both Lane and Mattera have seen the difficulties of the current campaign finance system. While there are matching programs in place for the funds raised by a candidate, a third party like the GP does not have the same reach as its Democratic and Republican counterparts. So if $500,000 raised by a party candidate is matched by the city, it pales compared to the millions raised by the established parties. Money for campaigns can often be a big determinant in who wins and who loses.

The GP also does not get the same number of opportunities to spread its message on public radio. “With no access to free public airways, a Green Party candidate can only touch a limited number of potential voters,” says Mattera. As for television reach, Lane noted that to appear on a televised debate, he would need to raise $100,000.

So what does a third party, in a two-party dominated city, do to get a message across? Its members go old-school and take it to the streets. “We’re doing this like we used to do 30 or 40 years ago, actually getting people on street corners and at transportation hubs, churches, schools, and letting them know, because they need to be educated,” says Lane.

The GP hopes to get voter support for the voting law changes it is advocating. One change would be to switch to a single transferable voting system. Under this system, registered voters would be allowed to make multiple picks based on preference. So if they vote for a Green Party member and they are not likely to win, their vote would then go to their next chosen candidate with a valid chance to win. By doing this, the fear of voting for someone who may not be a strong favorite in an election is nullified.

As of 2013 there were 7,000 registered “Greens” in the city. When new census numbers come out that number is expected to rise, in no small part, because of Bernie Sanders’ recent national success with pushing environmentally responsible ideas. Though, the GP hopes to improve not only environmental conditions, but the general way of life for all New Yorkers. “Environmental issues are just part of the whole problem with the city, from jobs, to affordable housing, to health care, education, the whole thing,” says Lane. Social, racial and economic justice are also key tenets of their platform.